While environmental regulations and policies are often fragmented across geographical, political, and social borders, environmental risks and impacts are transboundary. To fully address this paradox, science needs to reach across borders too.

Wilburforce Leaders, Erin Sexton, Chris Sergeant, and Jonathan Moore, are doing just that.

Chris and Erin are both research scientists at the University of Montana; Jon is a professor at B.C.’s Simon Fraser University. Though they live hundreds of kilometers apart, their geographical span and varied backgrounds provide a unique viewpoint for addressing some of the biggest challenges affecting the transboundary watersheds in the northwestern region of North America, including risks from mining, climate change, and land use practices.

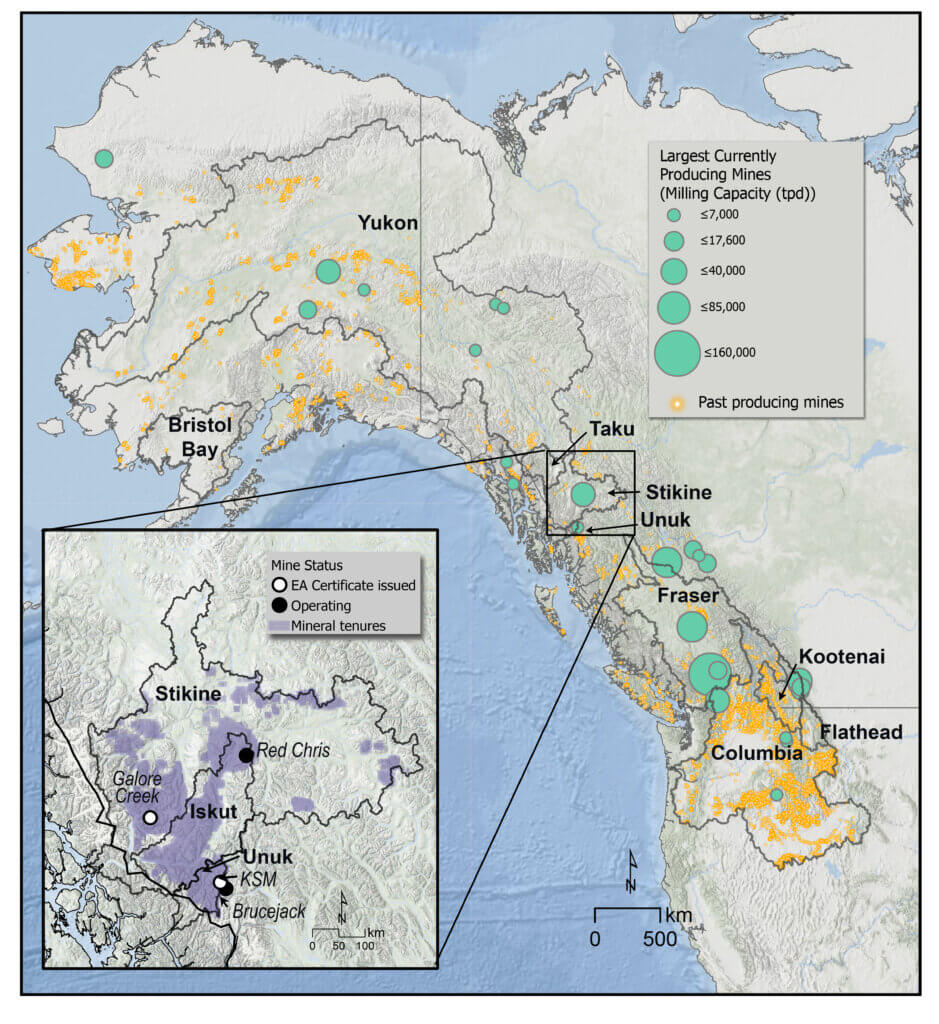

“If you connect the dots between where the three of us were located — Erin in Montana, Jon in B.C., and me in Alaska — the triangle that forms is a hotspot of important salmon populations and abundant mineral and coal resources. Yet, there’s not a lot of work done in the mining and salmon realm. That brought us all together,” Chris explained.

Current and past producing metal and coal mining locations in northwestern North America. (open access figure from Sergeant et al. 2022 Risks of Mining paper)

We recently spoke to them about their experience collaborating across boundaries. Specifically, they shared lessons from the 2019 interdisciplinary workshop that spawned the development of two important papers with over 20 co-authors from Canada and the U.S., each of which received international media attention: Risks of mining to salmonid-bearing watersheds and a policy letter published in Science in 2020.

The 4-day workshop, organized by Chris and Erin, hosted at the Flathead Lake Biological Station of the University of Montana, convened experts from diverse backgrounds and geographies dedicated to studying the impacts of mining on freshwater ecosystems throughout the region.

Diverse Expertise and Voices

“We really wanted to stretch our horizons and bring in not just science people but also policy experts, NGOs, and Indigenous experts. It was important to us to include all the people who were working on making a difference in the area,” explained Chris.

“We wanted to be transboundary in every way,” Erin added.

Collaborating across different backgrounds and geographies was a multi-layered exercise in trust – in the process, between the participants, and in themselves.

“As a participant, it was really amazing to watch the leadership of Chris and Erin. A collaborative process like that is a risk. There’s a lot of opportunities for it to go sideways.” Jon emphasized, “Getting all those people to understand each other’s expertises and bring it all together was pretty amazing. And brave.”

Finding Common Messages

In addition to the technical complexity of the various fields of expertise, they were also discussing a similarly complex and dynamic socio-political issue.

“With these international issues, there is often a deep history of pointing one’s finger either upstream or downstream. The inclusive process to co-develop and co-deliver this workshop and resultant papers with people from both sides of the border was a powerful approach,” said Jon.

They credit the efficacy of those challenging conversations on the strength of the relationships and mutual respect shared among the group.

“A lot of our success depends on relationships. Being intentional in your relationships is an important practice for any scientist who wants to have an impact on environmental decision making,” Erin stressed. “The worst outcome is losing relationships with people in place; It is hard to have an impact if you get siloed.”

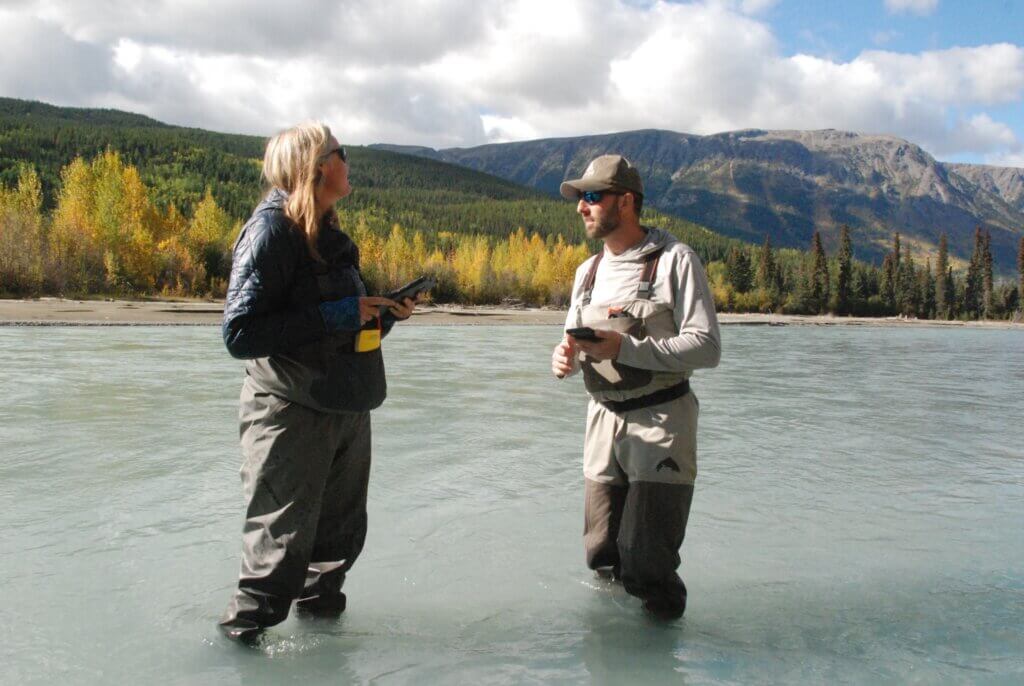

Connecting as People

They each highlighted the importance of building camaraderie, an invaluable — but often under-appreciated— element of effective collaboration. Intentionally connecting as humans makes it easier to lean into uncertainty, dive into difficult topics, and build meaningful relationships.

“It was important to not have people drift into their rooms after each session,” Chris stressed. “It was also so helpful to sit on the deck together with a beautiful lake view and engage in fun and meaningful conversations.”

“It’s really hard to network and build close relationships across vast geographies,” Erin added. “We were convening people who hadn’t met before and weren’t necessarily comfortable talking across fields all the time. Having time and a beautiful space to gather helped glue it all together.”

Even though they are usually hundreds of kilometers away, the three still manage to stay in close collaboration – in large part because of their willingness to engage as people, not just professionals. “It’s what collaboration is about. You’re not just working. You are sharing the excitement of the process,” said Jon. “We’re colleagues and friends.”

External Support

Cross-boundary collaboration takes a lot of time, effort, and support – things that are not always easy to find. For Erin, Chris, and Jon, the external support they’ve received from their institutions and funders has played a vital role in their ability to form meaningful collaborations within and beyond science.

“I want to emphasize the nature of our university institutions,” said Erin. “We have the intellectual freedom to build collaborations and partnerships in a way that would not be possible in an agency position with any of our respective governments. This is key to our collaborative work with Indigenous nations.”

“The support I get gives me the ability to really focus on the collaboration piece and intentional partnerships. That’s huge for making progress,” said Chris.

On the Horizon

Chris, Erin, and Jon continue to stretch their horizons.

Recognizing the need for cross-border science in transboundary rivers, they are excited to grow the existing work and relationships in key watersheds. “We are currently looking at collaborative research that combines different pressures including climate change, mining, and land use practices on watersheds that are fairly undeveloped. What does the future of those places look like?” Chris asked. “There’s going to be a lot of exciting work getting all the different viewpoints together.”

“This has all been an experiment over the past couple of years,” said Erin. “It is going really well, and there is a lot of potential to do more in other transboundary watersheds. We are working on balancing that with continuing to stay place-based and fostering the relationships that we currently have.”

“We are trying to take this really deeply place-based approach, but then also step back and take a 1,000 foot view,” said Jon.

Read more about their work:

- Western mining boom puts salmon species at risk, study warns

- New paper sheds light on mining’s impact on salmon and transboundary watersheds

- Mining risks for Pacific Northwest salmon murky due to lack of transparent data

All photos courtesy of Jonathan Moore, Chris Sergeant and Erin Sexton.