Like people, some science papers age gracefully, some plunge all at once into a sudden decline, while a rare few carry on unencumbered by the years, spry and punchy as ever. When I’m asked to recommend a single paper in science communication, it’s one of these seemingly ageless ones that I suggest: Fischhoff (1995).

Although specifically written on risk communication, “Risk Perception and Communication Unplugged: Twenty Years of Process” is broadly applicable to all those who communicate science. To my delight, it opens with a familiar phrase to biologists, “ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny.” In this case, Fischhoff poses it as a challenge: Rather than repeat the same developmental processes as our precursors, can we instead learn from the best available practices? If we understand the successes and shortcomings of those who have tackled similar problems, could we avoid the same pitfalls ourselves?

Yes, or so we’d hope. But it’s not easy. First, we have to be aware of preceding projects. Second, we have to be humble enough to admit we need help, and finally, we need the opportunity to observe the learning process. These themes may sound familiar – they form the foundation for my recent guest post at Nature, “A Tipping Point for Science Communication.”

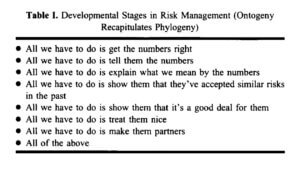

In the paper, Fischhoff catalogs the litany of approaches science communicators hoped would solve all our problems. Each developmental stage begins with a statement of “All we have to do is…”. If only we get the numbers right, or share them… clearly. If only we can show people it’s logically consistent with their choices in the past, or perhaps make them collaborators…?

Table 1 lists the progressive assumptions Fischhoff sees science communicators outgrow as their skills and understanding mature.

As I read and re-read this paper, I recognize my own beliefs in some of these stages, but Fischhoff takes away the sting as he acknowledges that each stage builds upon our awareness of the limitations of the previous ones. We must grapple with, and master, each fallacy in turn.

For me, the key insights from this paper include:

- ‘Data dumps’ may reflect an honest attempt to deliver results transparently. But when the raw numbers are confusing, these can be interpreted as obfuscation. Similarly, telling people more than they need to know can be perceived as deliberately unhelpful. Selecting and presenting decision-relevant information requires explicit understanding of your audience’s decision-making model.

- Values are an integral component of the risk communication process. Risks and benefits together tell a story that neither side does alone – and misunderstanding one is fundamentally different than rejecting the other.

- First impressions matter. Before we have time to analyze a message, we make judgments about the messenger. Word choice, nervousness, and other nonverbal cues are signals of a speaker’s competence and trustworthiness.

- As Fischhoff says, this is not just about taste, but also about power. “People fear that those who disrespect them are also disenfranchising them.”

- Relatedly, Fischhoff argues, often “controversies over risk are surrogates for concern over process.” And while it’s unrealistic to believe that effective communication will eliminate all conflict, the hope is that by applying the best available science of science communication, and learning from past experiences, we can have fewer but better conflicts. “A few people make their living from provoking or stifling controversies,” he acknowledges. “Most, however, just want to get on with their lives.”

I’m curious to hear from you though – what do you think? Which stages feel familiar? What other papers do you think are candidates for a “must-read” introduction to science communication?

For more recent thinking from Fischhoff, watch his talk from the 2012 Sackler Colloquium:

REFERENCE: Fischhoff, B. (1995). Risk perception and communication unplugged: twenty years of process. Risk Analysis, 15(2), 137–45.