A greeting card hangs above my desk that reads: “If I were a scientist working in a big lab, I’d shout ‘Eureka!’ every so often just to boost morale.” I keep it there to remind me of those moments of inspiration that not only boost morale, but drive the whole of science.

To me, those “Eureka!” events aren’t just reserved for medical breakthroughs or discovering new species, but perhaps even more importantly, are for making surprising connections among seemingly unrelated ideas to tackle a complex problem. Although some scientists have an innate ability to do this, others can start with just curiosity and a willingness to ask their colleagues, “What if we were to combine this with that?” After all, regardless of how much experience you have, solving complex problems requires dialogue across disciplines and perspectives.

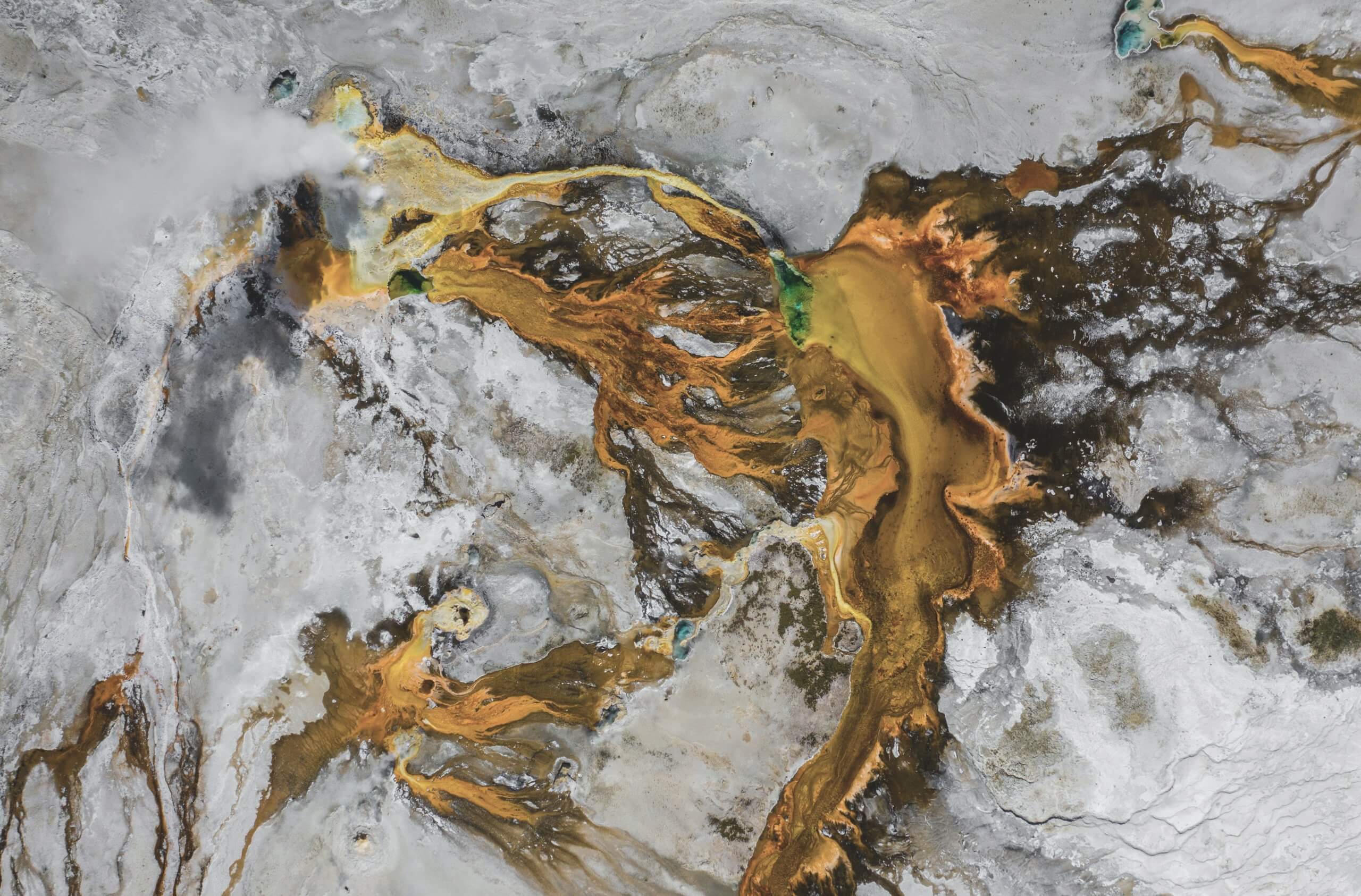

It’s a bit like experimental chemistry – at first the bottles on the shelves just seem like a dizzying array of options for endless combinations—but eventually you come to know enough about classes of molecules to understand how they are likely to behave in a reaction. This ability to see patterns (whether among molecules, methods, or ideas) allows for informed creativity that can serve as a catalyst to move science forward. But of course, just knowing which chemicals you want to combine isn’t enough… so here are a few more steps in my own lab protocol for catalyzing science:

1. Take inventory

Assessing the lay of the land by learning from other researchers (e.g. attending conferences, reading publications and blogs, following scientists on Twitter, and using other emerging tools) can be one of, if not the most powerful and consistent source of new ideas. It also tells you what’s already been done, how it was accomplished, and if it worked. Once you learn the landscape, you can find a gap to settle in and get to know your neighbors. (Although this may sound obvious, I’m often surprised by how narrow a landscape scientists tend to survey. I encourage you to go ahead and peek over the fence once in a while…)

2. Choose your supplies

The resources at your disposal (funding, institutions, personnel and technological capacity) are of course critical to determining the size and kind of problems you are able to tackle. But an often overlooked resource is the expertise of colleagues. Even if you do not plan an official collaboration, think about who you will call upon when you need to bounce around ideas, troubleshoot, or (if necessary) borrow a fire extinguisher.

3. Set up the experiment

After careful planning and preparation (and donning some safety goggles), at some point it’s time to mix the chemicals together and see what happens. Sometimes things fizzle out and sometimes you learn to live without your eyebrows for a while… but at least you’ll see the world in a new way. In other cases, you might help create something you never thought possible. Ultimately, it all becomes part of someone else’s inventory to set the cycle in motion again.

Although the term “experimental chemistry” might call to mind a lone figure in a lab, upon a closer inspection, all of the steps above have at least one major thing in common – communication. Communication about what has happened, what needs to happen, and how to make it happen. In fact, communication (in various forms) is the ultimate catalyst for new science. And, like a true chemical catalyst, communication is not consumed by the events it facilitates, but rather is free to continue catalyzing other reactions until the job is done. In this light, communication isn’t just an afterthought once the science is done. Instead, it’s what gets the whole thing started in the first place.