This post continues our series focused on science communication research. Instead of reporting on or recapping a single paper, we’re asking what the literature has to say about urgent or recurring questions in our field. This is inspired, in part, by John Timmer’s call for an applied science of science communication.

A flash of insight can be profoundly pleasurable. For me it’s a little pop that’s the mental equivalent of clearing my ears while diving. Sharing that same electric sensation with hundreds of others in crowd? Then the pop feels more like a champagne bottle, with our individual ‘aha!’s spiraling outward as a fizzy wave of tweets. At the Sackler Colloquium on the Science of Science Communication, Susan Fiske of Princeton University uncorked one such shared moment in her presentation about beliefs and attitudes regarding science when she began speaking about warmth and competence.

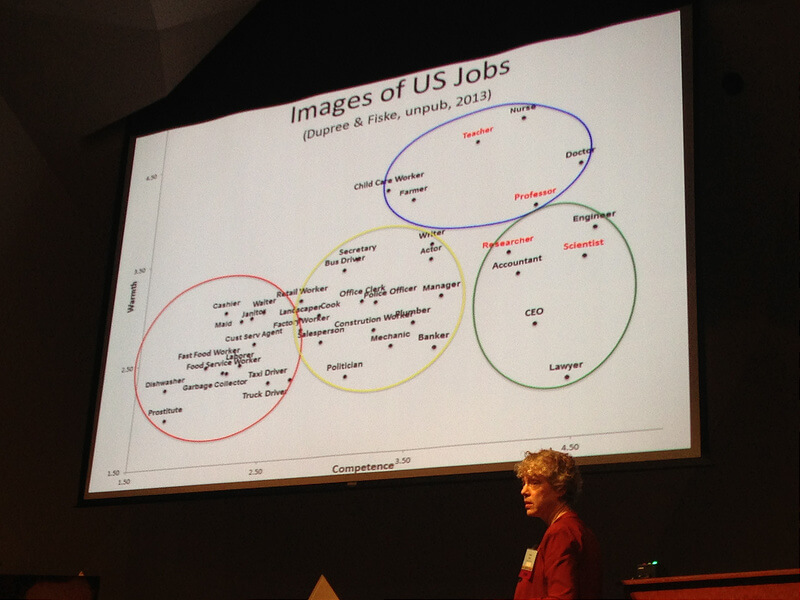

Within the first four minutes of her presentation dissecting when and how people make decisions, Fiske told the audience that scientists have the respect of the public but not their trust. Trustworthiness, she explained, is a quality produced by a combination of perceived warmth and competence. Warmth in this work is not exactly ‘likeable,’ rather, it refers to the judgments we make about person’s motives. Competence is their ability to act on those intentions. Scientists, Fiske says, are seen as competent but cold in comparison to other professions.

If you read our previous posts about trust in science, you know this is a topic dear to my heart. It’s also incredibly fertile ground for discussions of how we might start applying what social science tells us. Hearing Fiske talk, discussing it over lunch and coffee, and reflecting in the weeks to follow, I wanted to understand:

• What is this quality we call ‘warmth’ and why is it important?

• What do we know about how people view scientists in terms of warmth and competence?

• How can we – individually and collectively – counteract ‘cold’ reputations, if that is an important and valid goal?

The Research

This 2007 review paper by Fiske et al in Trends in Cognitive Sciences caught my eye with its unambiguous title: “Universal dimensions of social cognition: warmth and competence.” I encourage you to give it a read – the text is remarkably sharp and minces no words. Across cultures, with respect to individuals and groups, thoughts, and behaviors, warmth matters, a lot. In three quotes from the paper, here’s why:

1. “In sum, when people spontaneously interpret behavior or form impressions of others, warmth and competence form basic dimensions that, together, account almost entirely for how people characterize others… “

2. “Considerable evidence suggests that warmth judgments are primary: warmth is judged before competence, and warmth judgments carry more weight in affective and behavioral reactions.”

3. “competence and warmth stereotypes combine to predict emotions, which directly predict behaviors.”

In short, Fiske et al. argue that we have “decades of experimental social psychology laboratories, election polls and cross-cultural comparisons” all telling us that our instinctive judgments of warmth explain most of how we assess strangers, happen in split seconds and are more important than our assessments of competence, and directly predict behavior. The data on how scientists are perceived is as-yet unpublished, though Fiske showed some of it at the Sackler Colloquium.

Until we can take a hard look at the data, we should maintain healthy skepticism. But if it is true that scientists are seen as cold but competent, we may have a problem. My understanding is that this combination of traits can breed envy and jealousy, which psychologists link to “passive association and active harm.” When we talk about public trust or science as a brand, this is no minor issue.

It’s also important to acknowledge too that this literation about stereotype formation can lead to uncomfortable insights and hard conversations about race, gender, class, and other dimensions. Most social groups are not in the admired ‘very warm and very capable’ category. We must think carefully, and question assumptions that people are responsible for negative perceptions about them and could control those judgments if only they behaved differently. This is dangerous territory.

So What Do We Do?

We all know what it feels like to be working to make a good impression. When I asked twenty or so friends and colleagues to contribute to this post by sharing what they think signals warmth, they talked about smiling, eye contact, posture and body language, authenticity, and above all, listening to other people. This aligns with related work on impression management, finding that “when people want to appear warm, they tend to agree, compliment, perform favors, and encourage others to talk. When people want to appear competent, they emphasize their accomplishments, exude confidence, and control the conversation.” That quote comes from a paper by Holoien and Fiske with the intuitive but fascinating finding that people downplay positive impressions in the warmth dimension in order to appear more competent. Another group went so far as to include “You want to appear competent? Be mean!“ in the title of their paper. This seems to particularly relate to hypercriticism. I can’t help but think of how this manifests, for example, in journal clubs and job talks.

The bottom line for me is that if we are concerned about trust in science and perceptions of scientists, we must focus not only on competence but also – and perhaps more importantly – warmth. Rather than artificially exaggerating traits we think convey friendliness, scientists and science communicators should simply resist the tendency to emphasize their credibility at the cost of their personality. In short… perhaps the best advice is the simplest. Be yourself.

Journal Club

The methods, statistics, and theory of this kind of research is fascinating, but far outside my own expertise. We value your feedback and thoughts, so please take a look at some of the other papers that informed this post. I would love to discuss further:

• Becker, J. C., & Asbrock, F. (2012). What triggers helping versus harming of ambivalent groups? Effects of the relative salience of warmth versus competence. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology

• Çelik, P., Lammers, J., van Beest, I., Bekker, M. H. J., & Vonk, R. (2013). Not all rejections are alike; competence and warmth as a fundamental distinction in social rejection. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology

• Cuddy, A. J. C., Glick, P., & Beninger, A. (2011). The dynamics of warmth and competence judgments, and their outcomes in organizations. Research in Organizational Behavior, 31, 73–98. doi:10.1016/j.riob.2011.10.004

• Fiske, S. T. (2010). Venus and Mars or Down To Earth: Stereotypes and Realities of Gender Differences. Perspectives on Psychological Science

• Fiske, S. T., Cuddy, A. J. C., Glick, P., & Xu, J. (2002). A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: Competence and warmth respectively follow from perceived status and competition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology

• Vough, H. C., Cardador, M. T., Bednar, J. S., Dane, E., & Pratt, M. G. (2012). What Clients Don’t Get about My Profession: A Model of Perceived Role-Based Image Discrepancies. Academy of Management Journal