“Scientists are under increasing pressure to show the impacts of their work. They need to be able to hear from people who are speaking to the public so they can understand what the story of their research is and why – from the public’s perspective – it matters.” – Geri Unger, Executive Director of the Society for Conservation Biology

Scientific conferences are opportunities to share the latest research, amid a whirlwind of new ideas, data, and connections. The chance to meet new researchers and students, and interact face-to-face, is invaluable and it is why attendees and organizers alike are willing to invest their precious time and resources. Because so many great minds are all in the same place at the same time, scientific conferences also present an opportunity for scientists to share their work with the wider world.

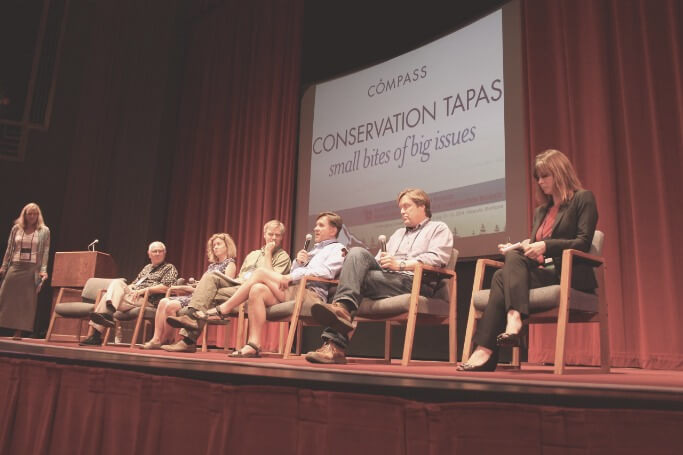

One of the main purposes of a conference is to communicate science, but mostly with others in your field or society. Meetings can also be traditional launching points for new projects and big announcements, and most conferences now host press registration and briefings. At COMPASS, we recognize the potential of conferences to facilitate the meeting of many different kinds of minds and different ways to communicate, but this usually requires breaking traditional molds. In July 2014, for example, our opening plenary, “Conservation Tapas: Small Bites of Big Conservation Issues” for the North American Congress for Conservation Biology (NACCB) introduced 25 journalists attending the meeting. Shoulder-to-shoulder on the stage, the journalists faced the conference participants: a powerful reminder that the world was indeed watching.

That opening panel was the culmination of a year of work with the Society for Conservation Biology to structure the meeting to promote meaningful interaction between scientists and journalists. First, we addressed the problem of attendance. Many journalists are keen to attend conferences, but shrinking newsroom budgets limit the travel of staff writers and freelancers alike. By organizing a journalist fellowship, we were able to cover or defray travel and accommodation expenses for 16 freelancers and reporters for The New York Times, NPR, Science and other outlets.

Second, we tackled social barriers that limit cross-pollination. To set the tone, we created a fast-paced journalist discussion panel and introductions for the opening plenary. This helped conference attendees better understand that the journalists were not merely there to cover the meeting, but to develop new leads and sources that seed stories for years to come. From the opening reception through the closing ceremonies, our team made personal introductions, livetweeted fascinating conference sessions, hosted thematic group dinners for scientists and journalists, and worked tirelessly to foster new and useful connections among attendees.

Hannah Hoag, one of the journalist fellows, told us that the deliberate integration of journalists into conference events made her more productive. “I appreciated how COMPASS made the journalists part of the meeting. I didn’t waste as much time finding researchers, explaining who I was and why I was talking to them. They came up to us instead. It turned the typical approach to reporting on a conference upside down,” she said.

By bringing journalists to the conference and facilitating their participation in the meeting, we were able to help the conference organizers transform the conference into a memorable opportunity for scientists to share their research, not just with their colleagues, but also with audiences beyond academia. We’ve seen the lasting impact of this kind of work, where scientists gain a broader understanding of the relevance of their work, journalists gain access to new sources for stories, and both have new opportunities to bring important insights to public conversations around environmental decisions.

Geri Unger, Executive Director of the Society for Conservation Biology, told us later that it was clear that the journalist presence helped the scientists to gain a broader perspective on their work. “Scientists are under increasing pressure to show the impacts of their work,” she said. “They need to be able to hear from people who are speaking to the public so they can understand what the story of their research is and why–from the public’s perspective–it matters.”