Prepping for meetings is important in helping you to have a constructive conversation – especially when the person you’re meeting with may have very little time or knowledge of your field of study. Another way to help your information stick, even after the meeting is over, is to leave behind a one-pager. A great one-pager catches their attention, starts a conversation, and acts as a reference.

A one-pager is a summary of what you will be talking about – the bullet points or headlines. It provides all the key information in one place, in a digestible package. Since you’re handing a physical copy to them, they’ll have it easily accessible, and at minimum, they’ll have to look at it for a moment after you leave, while they figure out what to do with it (though hopefully they’ll find it a useful enough reference to keep)!

A one-pager is also helpful for them if they want to share it with others in their office – they don’t have to just rely on their notes, if they took any, and you know it contains the key info that you wanted to share, so that if you aren’t able to get to one of your top points during the meeting, you know that they’ll still see it on the one-pager.

Policymakers get a lot of one-pagers, and you want to pique their interest so that they will contact you with follow-up questions. So have good content, articulate it clearly and concisely, and make sure it’s easy to look at!

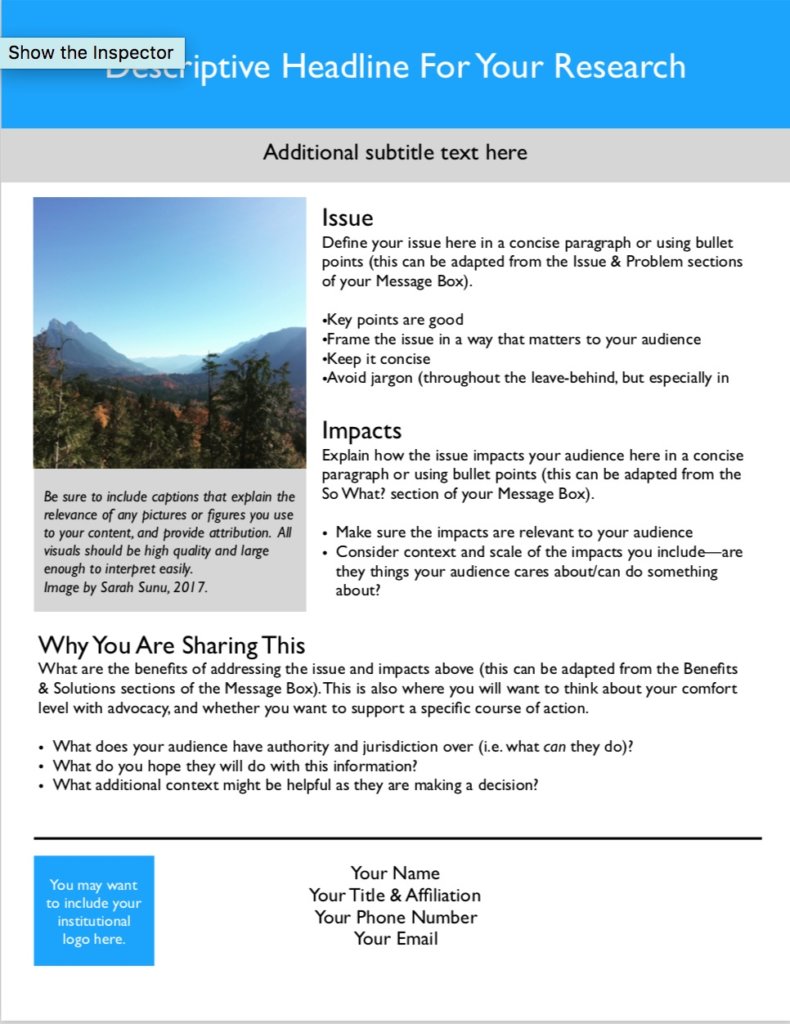

Below, we’ve put together an anatomy of a one-pager, so that you can see what to include, and we’ve also shared example one-pagers, with the kind permission of their authors.

Additional Tips For Throughout Your One-Pager:

- Start with the point, not with background or context.

- Be concise – headlines aren’t just titles. They should add meaning.

- Don’t talk down to the reader (avoid words like ‘Clearly…’ or ‘Obviously…’).

- Use good design principles: make sure that the font is large enough to read, and leave plenty of white space. Make it as easy to read as possible.

- Use color (but only 1-2 colors for formatting elements) and pictures/graphs where illustrative. Consider using colors that match your institutional logo, if appropriate, or otherwise neutral tones.

- For a polished product, try using Powerpoint, Pages, or Keynote (the same way you’d design a poster).

Getting ready for a meeting? We’ve shared a number of tips on the blog on how to prepare, from sending a clear and concise meeting request, to using the Message Box to figure out what is most relevant for you to share with the person you’re meeting with, to thinking through your answers to the questions that you might be asked, including the sometimes nerve-wracking “What do you want me to do about this?” question. Meetings are a great way to build relationships and share how your work can be relevant to policy.

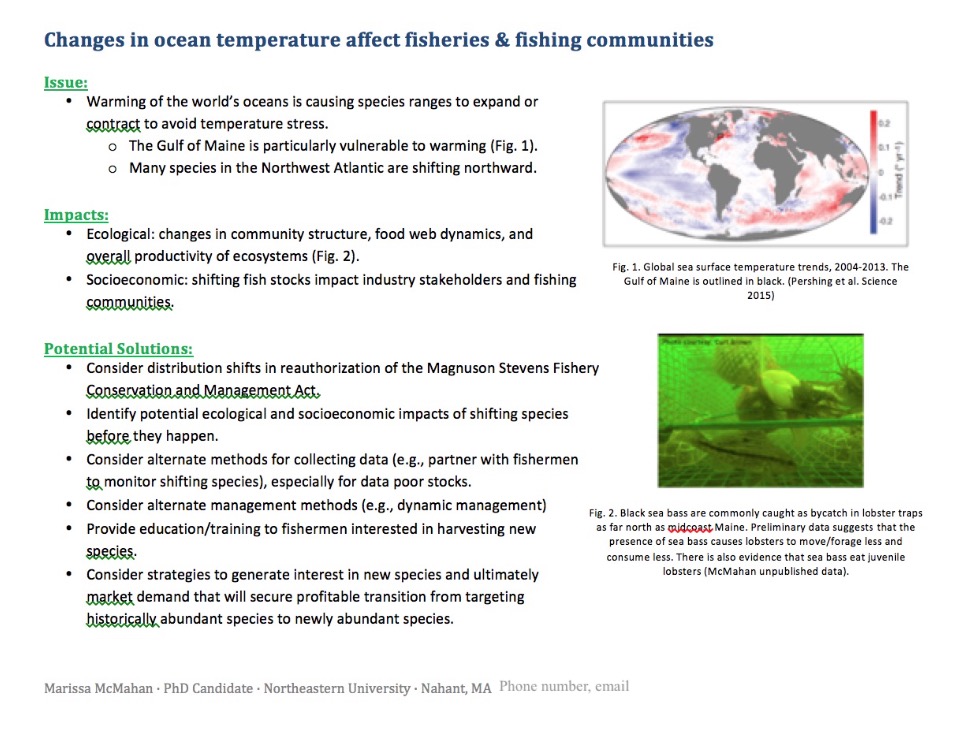

Example below from Dr. Marissa McMahan.